Excerpt

from Playing House: A Novel

Excerpt

from Playing House: A Novel

by Fredrica Wagman

Part One

How old were we then? I can't remember, very young, just children, just his laughing mouth, just his straight blond hair and always the blue shirt. His face was soft, puffy, almost as if there were no bones in it at all, not even all his urgency could put bones back into his face, red cheeks, country hands, peasant hands that were flat and thick, his nails bitten down to nothing.

He was the master, I was the slave who kept the steady beat, that was the game we played that put the urgency into his face and though I didn't know what we were after, I went with him. I kept going with him until it happened, until he made it happen rocking on top of me, pinning me under him, keeping me, pressing himself against me hard, on and on, weary and exhausted I kept going with him until it broke loose all over me and swallowed me up into it.

That first enormous thing of ecstasy, yes, then, so long ago. And the monumental shock of it, the bewildering incomparable immediate acceptance of it, the sudden understanding of what the secret is tumbling out of all the little hiding places in my body, this hint we're born with suddenly broke loose with him crouching over me, pinning me with the sunshine and the gleaming walls and the sparkling window glass -- and him.

The soft bedsheets of childhood suddenly yielded up a different meaning, a different message in their dishevelment. Now a bed became some brand-new thing, pillows that were dented where heads sunk into them said something. "Don't tell," they said. "You must never tell about this thing. Hide it away, smooth away the evidence. It's the Secret."

Never tell, never tell. We never said a word about it, not to anyone, not to each other and I thought then that something happened that no one else on earth had ever known, no one else on earth had ever fathomed or imagined and I knew that it was something that was forbidden. It was a secret monumental accident, but a forbidden accident. That by some strange stroke of driving luck we hit upon the secret of the universe and we were the only people who ever had. I thought then in some childish, illogical way that we were supreme-freaks, twisted, wicked, naughty, vile creatures who lucked out on some gigantic mistake no one ever allowed us to have the slightest understanding of, not in any way, no hint, no indications ever.

This amazing thing had been kept from us, protected by stern faces and silences, protected by warnings of going blind or madness maybe if we dared to touch, never touch, never go near there, bad girl, bad, bad girl. Stern hands pulling our wandering fingers away from the very first.

With scrupulous care we were made to believe that human beings merely walked or ran or hurt or ate or cried or did their jobs and waited, not discovered. They kept the real secret from us as best they could and yet we triumphed into all of it despite them, and it was ours.

Uncomplicated then, it seemed so uncomplicated that first time. So huge and simple, so overwhelming, like gratitude or hunger, it had no shadows, no veils, it was the product of integrity, of wholeness. I was a total person then, caught up into a total happening. Children we were, twins I used to think, more than twins, one person, my brother and I, separate from the rest of them, removed from them, outside the world, shameful, wicked, bad, lucky freaks we were, my brother and I.

I keep trying to remember on a little greedy inventory register how many times, exactly how many times like that, graphic times, the rainstorm times, the spring or winter, maybe summer times, how many? It's hard to say how many times, a lot of times that all melt into the memory of him, just him in a wordless tacit understanding about a secret that was ours. And then one day he was gone.

His bedroom empty, the bed was made and everything in there was left in perfect order with a stillness that was death.

I looked everywhere for him but he was gone. He went away. Boarding school my mother said. Boarding school. My mind held on to him as the rest of the world crashed into blackness all around me, something like how it must feel to be drowning in the ocean in the dead of night, hanging on to a phantom, trying to survive. "Endure," this one voice in my head kept saying, "just somehow endure."

I drifted out there lost a long, long time. A vague childhood after that of wandering and waiting, feeling seasons joylessly, receiving vague impressions, losing vague images, arriving for moments at imaginativeness and renewal and then losing this again to the one-dimensional and empty days living had become after he went away.

Homesickness became the only feeling I possessed, the nameless longing, the grieving, the counting days and hours and days again, the waiting mingling with wispy hope in some far-off distant way. What was I hoping for? I almost forgot. What was I waiting for, I couldn't say exactly. Something, something. A reunion maybe, a dream, a fantasy? I didn't know. It all had gone so far away from me, pain shrouded my brother's face so that I could hardly see him anymore, until loss and my brother became one thing inseparable, when reunion finally lured me and with it the search began. A search that was never satisfied, a search that was always intertwined with homesickness, the overwhelming meaning of my life became a wordless waiting, a search, and suddenly I looked around and my body was big, my feet didn't fit in the same size shoe anymore, the rooms I lived in were all different now, changed, this place is my home, isn't it? Yes. And yet I'm homesick.

This place that smells of feet and cigarettes and newspapers on the floor with a suffocating strangling closeness and it's all still dark, still vague, still one-dimensional and empty with homesickness destroying me.

Little crumbs are in the sheets, funny curtains on the windows over there with the night coming in, in blocks that change and shift and relocate across the ceiling. There's a dark green chair with all the cotton stuffing coming out, tired, weary, going fat and sloppy like an old army general still somehow at attention. The rug around the bed is blue now with crappy lanterns in the comers and in the center a nightingale is in a cage, a secondhand nightingale from a second-hand store, tired like all of it has gotten tired with nothing to take its place. The room that has no language anymore like voices without sound, food without taste, sleep without dreams, no dreams, no meaning, this man sleeping next to me, not crouching on me anymore, not suffocating me with his bodyweight, not burdening me any more, has taken all the meaning with him, fucking, fucking until he finished and dropped over, done, to sleep, snoring out the hours and the distance and the strangeness lying there. Who is he? I have no idea. Your husband, that's who he is. Yes of course, my husband, that's right. Can he save me? No, I don't think so, much as he'd like to, it's all too late. He goes too fast, much too fast, he isn't real, like the room isn't real. Real was a train going down the track that went too fast, that's all but lost from sight. Wait, I shout at it, don't go so fast, wait for me for just another minute, another minute might be all I'd need, but it doesn't wait, it's gone. just the smoke floating on a summer afternoon again. Alone, so utterly alone and flailing, reaching for a cigarette alone, flailing, reaching, grabbing for the smoke, hanging on to phantoms to survive.

I swirled round and round, the pink silk skirt would fly away from me, my petticoats were showing while I twirled. Weren't they remarkable all trimmed in lace, all starchy crinoline, dancing round and round out on the velvet afternoon? Look at me, I'm pretty, really, aren't I? My hair is black, my legs are long and straight, my skirts are flying round and round, I have a little satin sash tied in a bow around my waist, my body is still a tube, my arms are reaching up to touch the clouds.

Warm days rolling out of winter, spring again bursting out of eggshells tearing the thin stuff and filling the world with yellow. The sky hangs so close you can almost touch it with your fingertips, go ahead and touch it, it's close enough today, don't be afraid, fling yourself, no coats, not anymore, open your arms and spread your fingers wide and spin and spin and spin, school's done, there isn't school, not anymore, the crocus peeps up timid, the tulips are bellowing out in belching reds, all the goodness there ever was is here, right here, today, and I'm spinning, filling up the world with warmth again, hold it all before it's gone away, before it shrivels up like shadows and is gone.

"Where were you?" she said. "Where did you go? I've been looking for you for over an hour."

"I was here," I answered her. "Just here."

Her yellow eyes would look at me without a sense of seeing, like a blind person who has trained her lifeless lights to stop where the noise is coming from.

"I was just spinning in my perfect dress, feeling my skirts fly away from me, spinning round and round. I was only here."

"Where's your brother?" she asked me. "Where did he go?"

"I don't know," I answered her. "He's gone but he'll be back."

My mother clutched the shawl around her and went in. Walked across the wooden porch and I heard the click click of her high-heeled slippers, I heard the screen door bang her in, and in my mind I continued watching her, continued watching what she meant, trying to read what she didn't say, tried to look past her question to what she was really thinking. What was she really thinking?

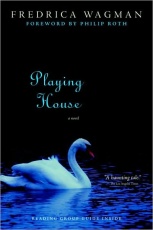

The swan was young then, she didn't come when I held my hand out to her, she didn't notice me, she drifted in the stream beside the house, remote and beautiful, and I watched her and I envied her how much she didn't need. I needed, enormously. I needed everything and suddenly I was aware of myself as hungry, as starving, and I spun around again to see only the closed screen door and no one there. What was my mother thinking.

The house that blinked its eyes, the huge and proud Victorian matriarch pitched across green velvet grass sitting on her haunches. There were porches and pillars and weather vanes, towers and shingles and wrought-iron grills around the roof, every detail was thin and perfect like a tune on a harpsichord at teatime with china cups and saucers and little golden spoons. The great marvelous ginger-bread house with bulging bay windows and steeples and shutters all in wood with a wooden porch along the front of her like a double chin. All pretend. So whimsical. The white curtains peeking out of the windows looked like the whites of eyes around the dark black coals that saw everything. The orange house with tan and brown, always pumpkin Halloween-time colors. That house, our house when we were little, where we saw the first of everything, where nothing ever changed, it seemed timeless, stationary against a changing, relocating sky. The seasons never seemed to matter, nothing ever budged in the breeze, it was always the same house with the same dress on, the same hat, the same bustle, a proper, sterile house that would not make allowances. Her house, my mother's house, that never had an odor and not a single blade of grass was ever out of step.

The earth stood still around it, snow never gathered there, the sky always hung in just the same way every day, the clouds around it never seemed to move, as if the whole thing was painted on the air and everything about it held its breath. There were no shadows, the rain didn't fall on our side of the hedges, only over there, across the property line. The trees were stationed vanguards that had no warmth or humor, just a job to do with crossed arms, no heart left, just principles. About the whole place there was a stillness, a permanency that was rock, that was fixed, immovable, but there was something wailing low, a sense of loss crying out in all the hollowness, in all the gingerbread and properness, in all the sterility there was a sorrow and an aching emptiness. There was no comfort there, no warmth, only a wailing in all the austerity, in all the perched importantness and it would catch me short when I would be dashing in from somewhere, rushing out of breath. Suddenly when I would be inside that house and I could hear it, this chill, silent, empty feeling would devastate me. I would spin around and look at all the shadows, at all the empty hollow rooms and hear it, this thing, this wailing. I would look for it as though I might be able even to see it, as though it had a face.

I would find my brother in the springhouse alone on summer days, always alone, no friends. I never knew what he did when I wasn't with him, what he liked, what he made or cared about. There never seemed to be anything except the waiting, the expressionless waiting, or that urgency. And he frightened me.

In a way he frightened everyone a little, everyone jumped when it came to him, what he liked to eat, how they tried to please him, they smiled at him a lot, they tried to make him laugh. He never made mistakes, no one ever scolded him the way they scolded me. They praised him just by the way they spoke to him. They favored him. When something didn't go his way he went off by himself down to the stream, to the swan. She belonged to him, she came to his hands only, took only his crusts of bread, left everything she was doing when he came and I would follow behind and watch him feeding her and I would watch the swan, remote and knowing, so beautiful, so easy in the water, so in command of herself, like he was, so indifferent. Both my brother and his swan seemed so at ease and in command of everything like they fit in their own skins and even chose the skins they would forever wear.

I was ten that autumn when the apple trees were heavy with their crimson fruit all falling down and he would grab the apples in a sudden outbreak of high spirits and start to throw them at me, laughing, hitting my arms and legs, and I ran away, running up the hill away from him and he kept throwing them and I heard him laughing, laughing, till I couldn't hear him anymore.

"Why are you crying?" I'd hear a voice from the top of the stairs but I never saw the face that said it. I'd never tell her why I cried, I never told a word.

There was a woods behind the school where I used to go, where the sun would come in broad bands of dusty gold like great enormous fingers through the trees. There I'd be able to pause a little bit and hold to myself all the things I was losing. Childhood, sun gold, bits of rocks I'd jam into my pockets and I didn't know then what was going to take their place. I'd stand alone, not wanting to let go of all of it and knowing still, despite my clinging, it was almost gone.

I looked up and saw the shadow of a cat hanging from a tree. I walked closer behind the bushes, creeping terrified up to it to make out the thing I thought I saw, and I saw him there beside it holding a switch in his hand. He didn't see me. The cat was hanging upside down by a rope, blood coming from its nose, my brother standing next to it. The cat was dead.

Later that night I lay in terror in my bed, my mother standing next to me. Yes, I told her what I saw, I had to, not to betray him but to relieve myself of the fear and terror I was suffering. "No," she said. That was all she said. It didn't happen, it was all a mistake, I was wrong.

It was as though I had put something into a drawer and closed it and when I opened the drawer seconds later the thing I put in there was gone.

He was fourteen then, long and thin, blond hair falling straight across his face. He was detached, he drew lines no one ever dared to cross. He drew them with his silences, he drew them with his boredom and his restlessness, with his vague contempt for everything except the swan.

Or else sometimes he broke out into these wild high spirits, sometimes he would come galloping out of his sullenness in a kind of wild different mood completely.

A wall ran along the orchard where the apple trees were growing, a low stone wall. He walked on it, I walked on the grass beside him, my hands trickling along the wall in front of his feet, running the tops of my nails along the ragged stone. He would be telling me stories when suddenly without a word, without an expression on his face, he drove the heel of his shoe into my fingers like he was putting out a cigarette, staring at my face contort in pain. His expression never changed except a little glimmer of a laugh when he released my fingers from his heel.

"No," she'd say, "he wouldn't do a thing like that, you must never tell stories on your brother."

"See," he said, "she'd never believe you anyhow. I'm always right."

His room was at the far end of a sunny hall. There was a bed and a dresser and a desk, shelves for books and little things all over that belonged to him that had a place, that never moved, that he kept in minute and perfect order. I would open the door and find him on the floor cutting things out of magazines and making neat piles of what he cut. I'd find him drawing pictures of unimaginable detail with strange lines and circles, animal faces over monstrous bodies, thousand-legged creatures or grotesque people, pasting words and faces on them from the magazines and he'd tell me to come and look. There were always stories that went with them, stories about beasts and storms and being eaten alive, that somewhere in the house, in this great old scary windy house the creatures lived and waited and if I wasn't very good he'd let them out on me to eat me and devour me, and I ran screaming from his room and then I'd find him standing in the doorway of my room looking at me. How old was I then? Still ten I guess, maybe eleven, I can't remember, I can't say exactly. He was waiting then, standing there, and while he waited, the expression on his face slowly changed to urgency, slipping over him like a stocking over a foot and then the leg. He frightened me and he fascinated me both at once, and I'd remember what it felt like with him. I'd remember the little ripping electric waves rolling over me again and again if he would only climb on top of me and begin to rock, pressing hard against me, pinning me there, holding me down on the floor, on his bed, down in the springhouse. We could hear my mother calling. I'd stir and he'd put his hand over my mouth and crumple over me, gasping and exhausted, till it happened, again, another time, just once more, until he went away.

A little bunch of flowers at my bedroom door, a book with funny pictures in it, a thing of dusting powder, an envelope with seven dollars, one of his sweaters, a camera he brought me from New York, toys, always a little present, no reason. "Come and get it," he would shout, and when I vomited he held my head, and he'd bring me ginger ale, and he'd sit with me until I fell asleep.

"You'll never leave. You'll never go away?"

"No," he used to say, and he'd look away.

"Maybe we can get married one day?" I asked him.

"No," he said, pushing the yellow hair off his face, turning away from me, gentle, smiling, soft face that had no bones in it, pink then from the thing we had that happened not completely gone from him. Still flushed. "It doesn't matter," he would answer me, "brothers and sisters can't be married, don't you know, if they do, then their kids have blood diseases, become idiots, it's not important anyhow, it doesn't matter, it never will."

"Don't go," I used to say to him. "Don't ever go." But he only used to turn away and bite his nails.

In my mind it seemed as though he were the one who commanded the sun to rise in the morning and set each night exactly the way he had decided it should. He knew everything. He was the one who invented certain words that everybody used, words like "certainly" and "not particularly." He commanded people just by looking at them or by being silent, and his moods, his shifting shadows, were what the days consisted of, there was no weather, no winter or summer, it was just his moods. He created atmospheres, everybody worried about him, everybody tiptoed around him, around his frowns, he was the center of the universe, all the rest of us made up the borders.

We had a sister who had red hair, who lived alone and talked to herself, who never liked to lend things or let anyone in her room, who cried a lot and finally one day killed herself.

She had the same strange yellow lights my mother had that could focus where the noise was coming from but never saw a thing except her own gray shadows going up the stairs. Sarah. She was the oldest. The train went too fast for her too, she couldn't grab the smoke. Sometimes the train just goes too fast racing along the steely tracks away, over the flat, low, gray-green night through the brownish trees and little canals that grow along the side of railroad tracks, empty tracts of land that border emptiness, an emptiness not touching people, not holding them in your arms and hearing words that can save, wise words, wisdom words, real meaning words. Combing your hair and fixing ribbons in it to make you beautiful, straightening out a skirt and seeing it fall just right, choosing the perfect pair of shoes and smiling in a mirror to see how wonderful the whole thing happens to work out when everything is real, when everything tastes good and makes you warm and comfortable with a little hint of joy lurking in there somewhere, almost breaking loose. It used to be that way when spring would come again breaking out of eggshells, bursting out in yellow lace, in brand-new leaves and velvet grass again, twirling round in my pink silk skirts and feeling them fly away from me out there, reaching up to touch the sky.

But now the train is racing down the tracks too fast. How long have I been living in a fog? How long have I been grabbing after smoke? And far down is the street.

The window is open with the night coming in, the sleeping man is out of reach, sleeping in his satiation, snoring out the emptiness. Who did you say he was? My husband, that's right, my husband.

"Does it run in families?" I turn to him, waking him. "I mean about my sister?"

"No," he says, "how many times do I have to tell you? No." Why can't I trust him? I'm thinking. Because he's so much a total stranger to me, this husband-stranger-man. I have no anger for him, no contempt, nothing. He doesn't matter, he can't save me, he's here by mistake and if I close my eyes in the morning he'll be gone.

No, he won't be gone, day after day after night after weeks and months and years with your hair getting gray and chins coming out and stomach trouble and trouble walking he won't be gone. He'll still be there sleeping next to you, foreign and inaccessible with nothing to say that helps, that helps getting old and hurting and coming undone or falling apart.

He could never put me back together. If I ask him what time it is, or what day it is or what year, he'll answer me. In the morning he'll wonder if I took my pills but if I ask him if it runs in families -- destruction, suicide, yellow eyes that never see but only focus where the noise is coming from -- if I ask him why it's all this way, where the road took the crazy twisting detour into woods and brambles, into tangles and rocks with gigantic laughing faces and cats hanging dead beside a stream, or was it in the woods? No, not a swan, a red-headed girl who never liked to lend things, a dead cat, the sun-filled room at the far end of the hall, my mother looking at me.

"Where is he?" she would say, "where did he go?" Where did he go? I asked her. The dead cat, the switch in his hands and Sarah lying on the kitchen floor in a fur coat, dead, twenty-five Nembutals pumped into her, clutching car keys in her hand. Where would she have gone? Where was she headed for when she dropped over holding the car keys? No, he doesn't know the answers with his shoulder hugged around the pillow. My turtle husband hiding in his tortoise-shell around him, he never knew those answers. My Turtle in his shell would only mutter from his sleep, "Not this again."

"Can I have a cigarette?" I ask him sleeping there. "Would you get a cigarette for me? There are more on the table over there but the window's open and far down below is the street and it scares me. I'm afraid to move out of bed and cross the room to get the other pack. I'm afraid of the window, it might eat me up, it might devour me."

"Not this again," he says from his pillow bosom he keeps clutching. "You'll be all right, just take the pills. We're all destroyed. We all have monsters and dead cats and hollow rooms, it doesn't run in families, it comes from being alive. You have to be strong, you have to have a sense of humor."

"Can I have a cigarette?" I scream at him. "Please, get me one, I'm scared, I'm terrified, she couldn't get the smoke. The train went much too fast for her, don't you understand, she was crying all the time talking to herself, but she was my sister, she was my sister. You can't know what I felt when I saw the cat hanging there, when I saw him standing next to it and I kept trying to clutch the sun bands to me losing them, standing there, losing the woods and childhood and not understanding. I didn't understand."

The Turtle gets out of bed, out of his sleep, and ambles across the room, fumbling in the dark for the pack of cigarettes. "You're hungry," he says, "you need to eat something, what do you want?"

"No," I answer him, "not hungry. I'm stiff and suffocating and weary, my whole body feels like a toothache. I don't want anything to eat, but thanks, don't leave, don't go away."

He lights a cigarette, I see the orange dot in the dark with him behind it looking out the window and thinking to himself, Not this again. `

The above is an excerpt from the book Playing House: A Novel by Fredrica Wagman. The above excerpt is a digitally scanned reproduction of text from print. Although this excerpt has been proofread, occasional errors may appear due to the scanning process. Please refer to the finished book for accuracy.

Copyright © 2009 Fredrica Wagman, author of Playing House: A Novel